The TV show Grand Designs has been gracing our TV screens for almost 25 years, providing us a window into the life of those people who dare to build their dream home. From a converted water tower to a lighthouse, or a house made out of shipping containers, Kevin McCloud has taken us the viewer, in his own wistfully philosophical way, along for the ride. And in doing so catalogues the inevitable emotional roller coaster of budget overspends, weather driven delays, unforeseen problems and the harsh reality associated with living in temporary accommodation for way longer than you had ever intended (often with a young family).

Sitting in my ivory tower, as a construction professional, I’ve always found Grand Designs a difficult watch. As I am one of those many people who sit and shake their head at the TV issuing stout advice about how they could have done it differently, to at least avoid some of the inevitable calamity which will surely ensue. And more often than not, does!

Grand Designs may feel a million miles away from most of the projects I have worked on throughout my career, however my recent binge of their back catalogue got me thinking about some of the parallels we can make, and perhaps why the ups and downs of bespoke house building, by everyday people, might not be so far from the reality we experience as professional builders. Especially when it comes to the UK’s track record of delivering major infrastructure schemes.

By the very nature and scale of the undertaking, major infrastructure schemes are complex, and are often completely bespoke. Making them inherently challenging to design, construct and commission. In many cases we, as an industry, are doing something for the very first time, so a lot of careful thought and planning is needed, and even then we can expect a few surprises along the way. But should this really be the case? After all we are professionals, and this is what we do for a living.

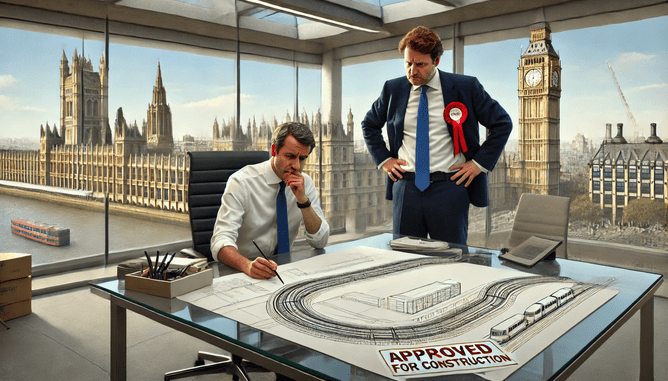

Having been involved in one or two major infrastructure projects throughout my career, one of the things that has always stood out to me is how complex they are. And when I say this, I’m not just referring to the technical challenges, but moreover the politics surrounding absolutely everything associated with it. As a bystander it would be easy to think that the process of bringing a major project to bear would be a well-trodden path, starting with someone in the Government identifying the need to build, for example, a new high speed railway from London to Manchester. However, this doesn’t seem to be the case. So much so that a myriad of politically driven complexities, to me at least, seems to be the real driver behind many of the challenges these projects face.

Take for example Crossrail (Elizabeth Line), which was widely reported in the media as a good project gone bad. Indeed, the cost crept from £15.9bn to £18.9bn, and the programme went out by circa 4-years, so bad is probably as good a word as any to describe the final outcome. Yet when you do some research into what happened, much of it focuses on the technical challenges associated with delivering such a complicated scheme. And whilst I certainly give many of those articles credence, I see that take as more of a consequence, as appose to the actual root cause of the problem. Yes, they could have planned better, yes they could have made more risk provision for the many unknowns, yes they could have had a more well progressed design before starting, but none of that happens unless the politics allows it too.

You see politician’s like to use projects like Crossrail as a political talisman, and in doing so make commitments on sign-off, budget and programme sometimes years in advance of actually being in a position to do so. Sure, everything must start somewhere, but this eagerness to be the party that get’s something implemented seems to be placed far ahead of the bigger picture, yet sets the tone for the years that follow. Crossrail was given the green light in October 2007, by then Prime Minister Gordon Brown, placing the £15.9bn budget and Dec-2017 opening date firmly in the public eye. Meaning that from that moment on any deviation from that budget or that date would be the measure of success and failure for the entire scheme, at least in a political sense. Of course the scheme was plagued with a myriad of other issues (far too many to mention here) which all contributed to the final result, yet I am a firm believer political pressure played a major role throughout the project’s lifetime, which is something that rarely gets a mention. That project saw 5 Prime Ministers, 3 Mayors and several changes of leadership through it’s lifecycle all of which will have impacted the way in which the scheme was managed and messaged. Not to mention influencing the way the project was perceived by the general public.

I’m conscious that I have brought focus on Crossrail, however I could have picked any number of schemes such as HS2 or Sizewell C to place emphasis the point I am trying to make; that the political process is not conducive to the successful delivery of major infrastructure projects. More often than not adding undue complexity and pressure to what is already a complex undertaking.

I started this piece by taking a light-hearted look at how Grand Designs projects might have some parallels with major infrastructure projects, and sure, perhaps the outcomes are similar but the journeys to the outcome are entirely different. The people undertaking their grand designs are often complete novices with little more than a dream, some money, and wishful thinking to drive them forward. It’s therefore hardly surprising that things take longer and end up more expensive than they first envisaged. The infrastructure sector in the UK, by contrast, contains some of the brightest most forward thinking professionals I have ever comes across with more than enough skill and intelligence to deliver projects at the cutting edge of human ability. This capability is however sadly overshadowed and suppressed by a constantly shifting political landscape that likes to meddle with ongoing projects, making them more challenging that they really should be.

I know it’s easy for me to stand on my soap box and bleat on about how political interference is more of a hindrance than a help, however I am also a realist and understand that this process is sacrosanct to our constitution sitting at the very core of everything that makes the UK what it is. It would therefore be naive of me to expect that should ever change in of itself. What perhaps could change, once the project need is established, is the introduction of a clearly defined national roadmap to design, cost and programme certainty, which is known, understood and applied consistently to all major infrastructure schemes. It would incorporate known points of political intervention, but also and more importantly define the deliverables at each stage which would ensure a project does not proceed to the next stage without having had the correct level of scrutiny. Thus shoring up what is important, when it is important and helping steer projects with the level of rigour we need to ensure cost and programme certainty.

Anyone who has ever worked on more than one major infrastructure project will identify with the fact that we seem to have this habit of needing to reinvent the wheel, with leadership writing plans that we have all seen written before. And I’ve lost count of the amount of humdrum conversations I have had with colleagues who have scars from the last time they followed such a plan, giving off the uncomfortable yet inevitable feeling that they know what’s coming next.

To me, a nationally consistent and sufficiently detailed approach to the planning and delivery of these infrastructure schemes is the key to delivering budget and programme success. It must take heed of lessons learnt as well as consider the views of our world beating supply chain, and moreover become something which embodies a world class approach to the delivery of our national infrastructure. Else we all risk continuing to look like inexperienced everyday people, just trying to deliver their dream home, with little clue about what is really going on.

By, Ben O’Connell

Commercial Director

Vinovius